When painting demands too much

Radu Oreian: Vertical Vertigo

January 23 – March 21, 2026

Art Encounters Foundation

Timișoara, Romania

Trained in graphics and painting at the University of Art and Design in Cluj-Napoca and later at the National University of Arts in Bucharest, Radu Oreian’s practice remains anchored in classical mediums while probing how history, ancient myths, and archival structures shape our understanding of humanity. Yet in his latest exhibition, humanity does not appear as subject or image, but as a condition of proximity—it is from this tension between human measure and visual closeness that the exhibition unfolds.

Born in 1984 in Târnăveni, Romania, and currently living and working in France, Oreian has recently opened his most cohesive exhibition in Romania to date. Curated by Diana Marincu and presented at the Art Encounters Foundation in Timișoara, Retinal Vertigo marks the artist’s first major solo exhibition in the country, bringing together paintings and drawings produced between 2016 and 2026.

Proximity as Discipline

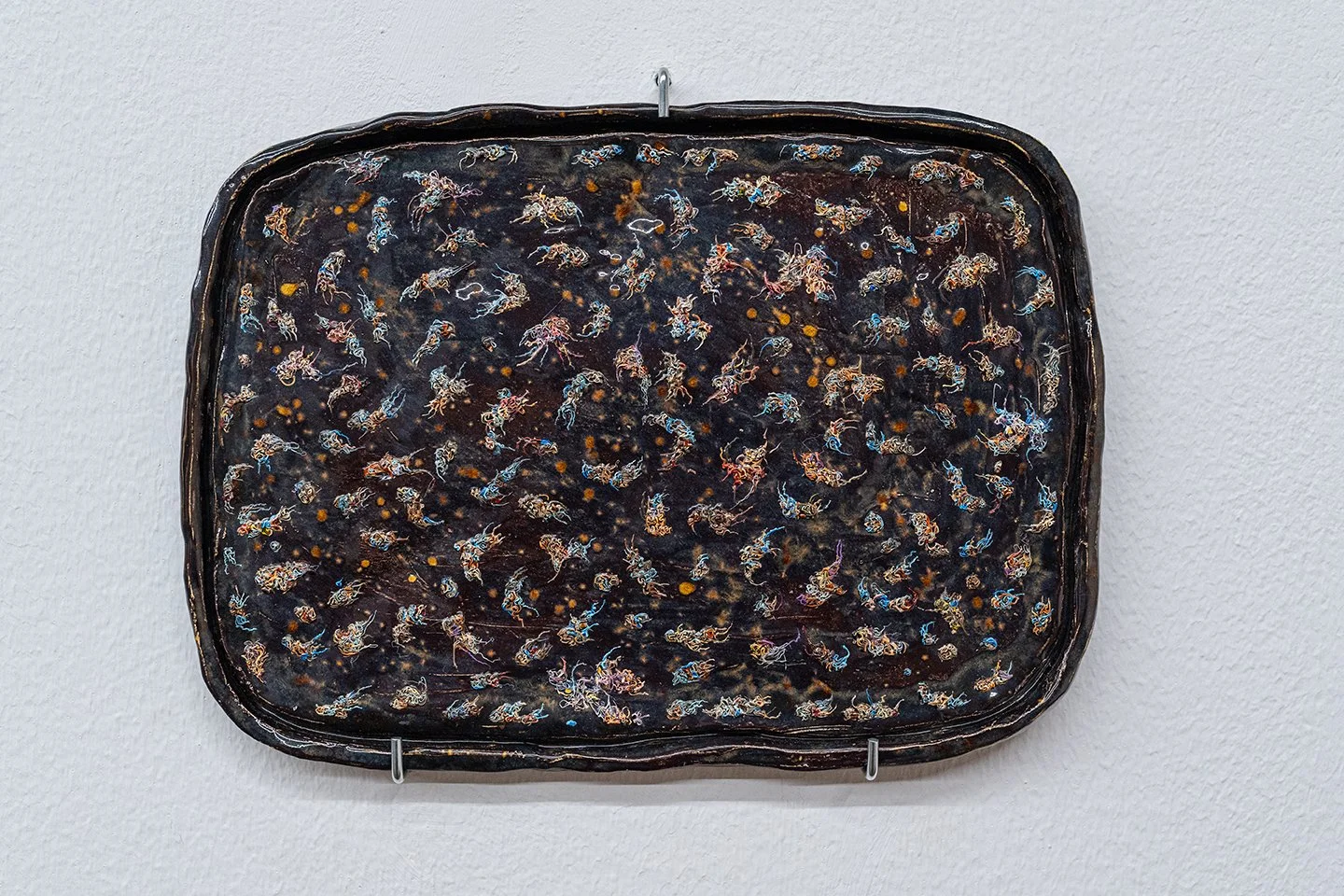

The enforced intimacy produces a paradox: the closer one moves toward the image, the less mastery one gains over it. Proximity in Oreian’s works does not clarify; it complicates. The surface resists legibility even as it solicits attention, converting looking into a sustained, effortful negotiation. In this sense, Oreian’s paintings refuse the comfort of optical distance and deny the viewer the privilege of overview. There is no sovereign position from which the image can be grasped, because it becomes simply amorphous, as in the experiments Farewell to the Thinker of Thoughts (2019), the series Vectorial Microscript (2013), or Vectorial Miniatures (Triptych) (2020). Instead, meaning is fragmented, dispersed across micro-events of texture, trace, and chromatic decision, each demanding its own moment of care.

What emerges is a regime of looking that is ethical rather than aesthetic. The viewer is invited to consume the image and to serve it—to bend toward it, to linger, to submit time and bodily presence. This service is neither rewarded with narrative resolution nor with visual plenitude. On the contrary, the painting withholds. It trains the viewer in restraint, in patience, in a form of attention that borders on obedience. The image does not open itself; it must be approached again and again, through repetition rather than revelation.

Devotion, Strain, and the Cost of Attention

This is where the devotional structure becomes unmistakable. Like the icon, the painting does not represent so much as it addresses. It looks back—not metaphorically, but structurally—by reorganising the viewer’s posture, breathing, and spatial relation to the work. One does not stand before the painting; one leans into it. The act of viewing becomes a choreography of humility. Any desire for interpretive mastery is quietly disarmed, replaced by a disciplined attentiveness that resembles prayer more than critique.

Yet this devotion is unstable. The longer the viewer remains within this regime of closeness, the more discomfort accumulates. Reverence slides into strain; care into compulsion. The painting demands too much. It implicates the body beyond what feels permissible, pushing attention to the threshold where fascination becomes unease. The surface no longer reassures; it insists. The viewer becomes aware of their own proximity as excessive, almost improper, as though violating a boundary that the painting itself has both erected and invited to be crossed.

This tension—between invitation and refusal, devotion and discomfort—is where the work’s critical force resides. Oreian’s paintings do not simply ask to be looked at closely; they expose the costs of such looking. They make visible the labour, the faith, and the submission embedded in acts of attention we often take for granted. In doing so, they unsettle not only the viewer’s body, but also the economy of viewing itself—an economy that typically rewards speed, recognition, and visual consumption. Here, attention is slow, demanding, and unresolved. And it is precisely this unresolved closeness that leaves the viewer unsettled, suspended between belief and resistance.

Mincemeat, Saturation, and the Exhausted Eye

He uses microscopes to probe and enlarge paint drops (“I used my phone to see the enlarged images, because I wanted a deep dive into the microcosm of the image”). In a strange way, his demeanour seems moulded by his interactions in the West. I sensed a pre-orchestrated tone as he guided me through the exhibition, a rehearsed cadence that framed both the works and his explanations. I usually resist hearing artists speak at length about their training or technical accomplishments. What I want instead are conceptual openings, thought processes, nervous breakdowns, dishevelled narratives, detours—paths rather than certainties. Oreian knows his work very well, perhaps too well.

This, however, has little to do with what I think is largely overlooked in his work: the drenching nausea of the surface. The vertigo that he and Diana Marincu inscribe in the title Retinal Vertigo feels less like a metaphor than a diagnosis—a proposal for a new condition. And we like that, don’t we, vertigo. After all, it displaces us for a moment, ejects us from ourselves, deposits us briefly on the sidewalk of existence.

The work For You (2025) functions as a graphic quotation of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s accomplished portraits: composite, allegorical faces assembled from fruits, vegetables, and plants—playful yet erudite constructions that fuse illusion, nature, and wit to explore identity, seasonality, and transformation. Oreian’s work operates here, to an extent, as a variation. Another descent into an abyss of drooling marks, liquefied tensions that crawl across the surface of the drawing. Yet they do not fully crawl into my psyche. The representation acts more like an intravenous infusion—administered to maintain the fog that carries you into the next room. It sustains a condition rather than rupturing it.

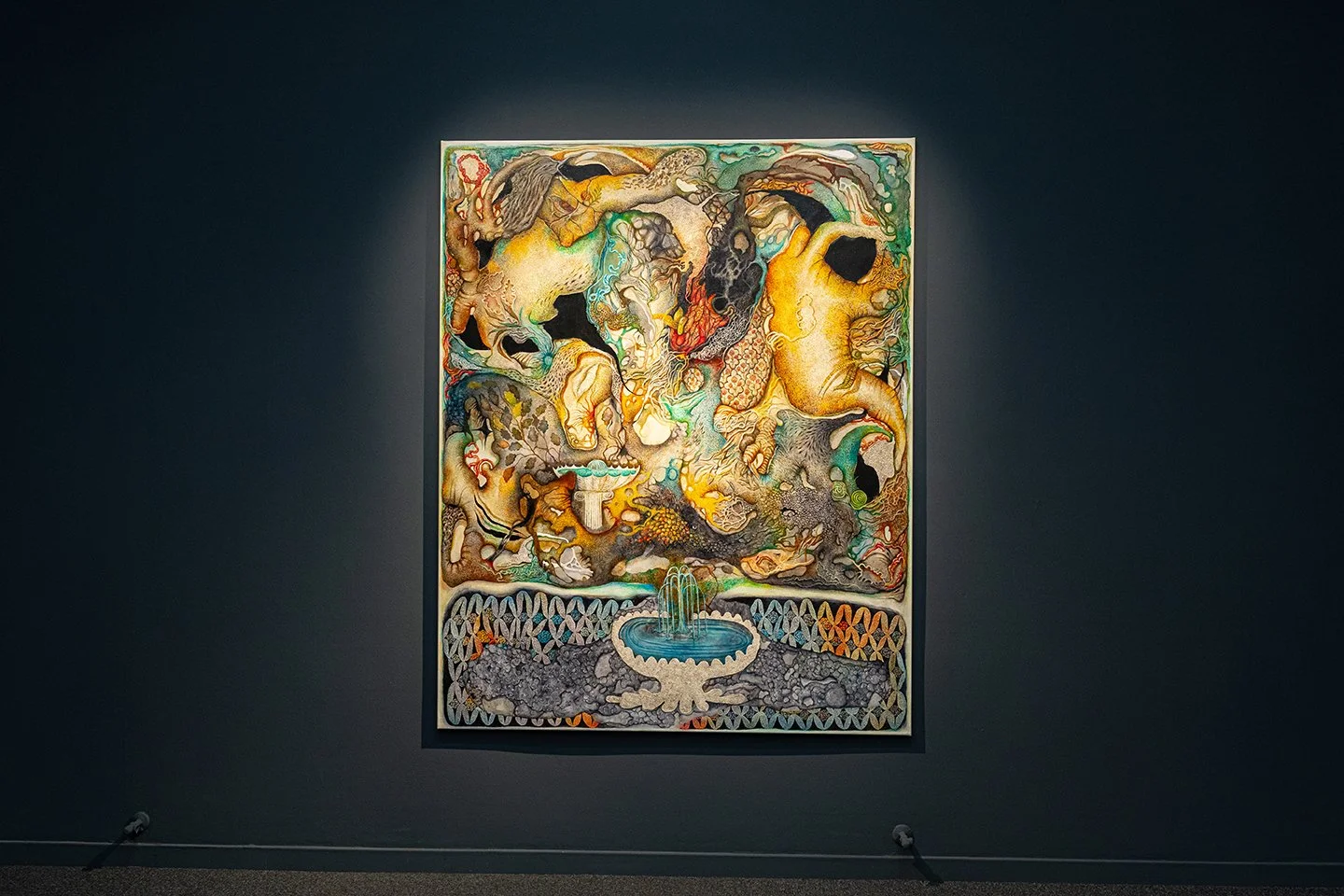

In Plot in the Garden of Delights (2017), we encounter guts and spillage intertwined with symbols of rebirth and death. The design of the twisted mincemeat recalls cerebral gyri—a car crash of flesh and cognition. There are no poignant visual registers here, no single arresting image to hold onto, but rather a recurrence of the universe turned upside down: two monstrous entities seemingly engaged in a perverse photosynthesis of plants, organic matter, and ornament.

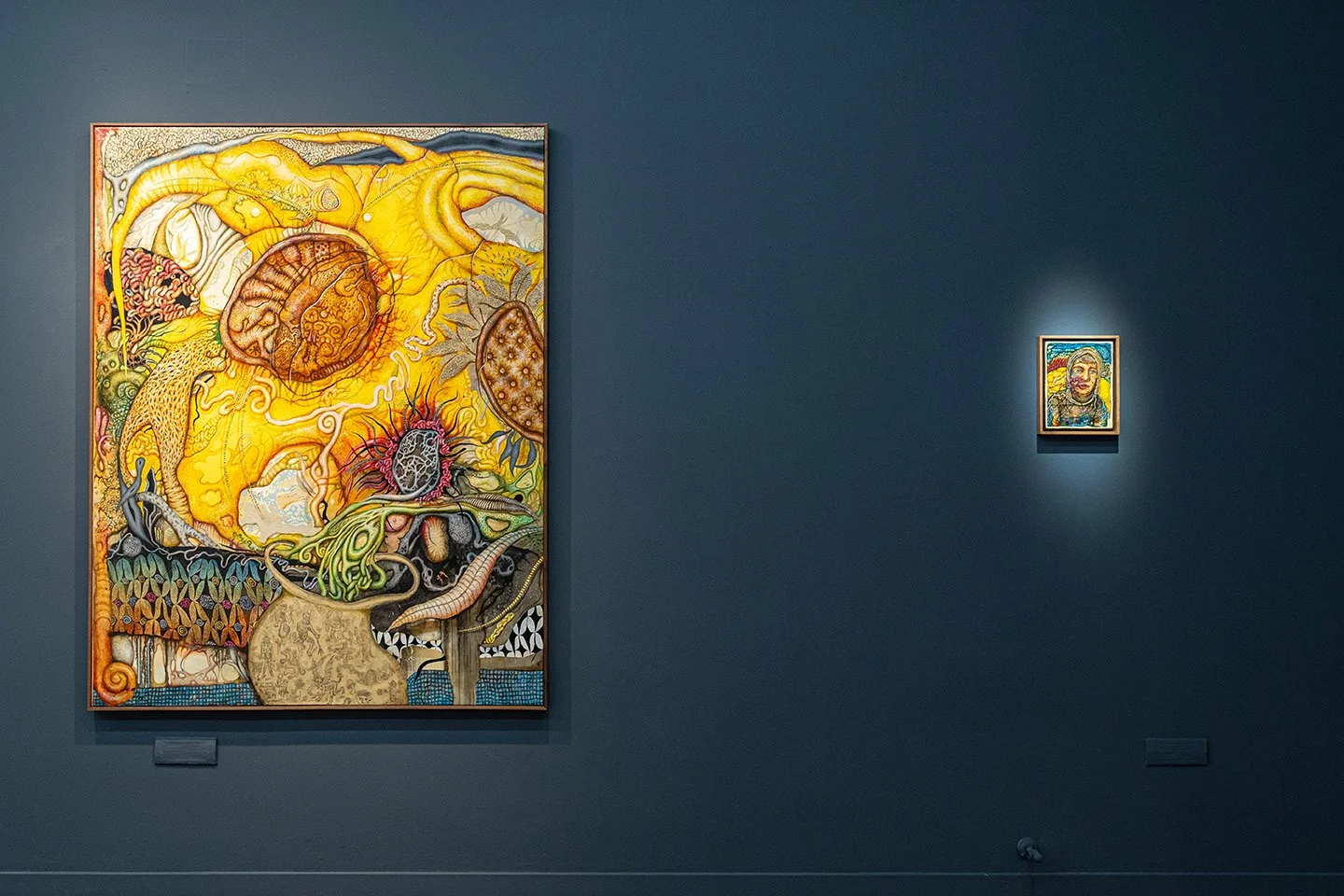

This dynamic becomes more compelling in the unframed canvas Self-Portrait under a Palm Tree, positioned centrally within the exhibition. Oreian describes it as “an abstract landscape created by highly organic textures, almost like a mirror of ourselves… I chose to present it as a tapestry rather than as a painting—like a fragment of a fresco.” Once again, however, the texture he refers to is that of the mincemeat—yet it is articulated from the position of the viewer rather than that of the maker. “After seeing more than ten exhibitions a day in Berlin,” he recounts, “one morning I looked at the ceiling and saw this mincemeat revealing itself to me.” The origin of the image thus lies not in production, but in saturation.

Oreian’s rationale for the notion of mincemeat is fundamentally cultural. It is here that he injects his perspective on art—not as an autonomous maker, but as an art consumer. His exhausted self speaks. Consuming art becomes as consuming as making art. Or, more bluntly: it is simply consumption. The surface registers overload, excess, and fatigue. The work mirrors a condition in which visual culture is digested, regurgitated, and reconstituted endlessly—less as critique than as symptom.

Units, Repetition, and the Turn to Ritual

The small unit—whose role is multiplication—is fully at work in the wall installation featuring interactions with found drawings from an acquaintance who suffers from autism, where repetitive elements accumulate to form a composition. Here, Oreian moves toward the negative space of the found drawings. Rather than intervening directly on the original page, he leaves it intact and instead covers an adjacent sheet with the positive image extracted from it. This displacement establishes a more conceptual engagement with time, materiality, identity, and labour.

It is in this gesture that Oreian’s systems of measurement and scalable units demonstrate their real strength. The work no longer depends on representation; it operates through transfer, delay, and repetition. When representation drops dead, that is precisely the moment his craft enters the arena of the ritual. When abstraction and figuration live on the same canvas, explicitly, their agent of bonding is the technique, which makes up for a situation where function merely serves as a pretext for texture, deflecting attention and animating the surface into oblivion without fully accounting for its own necessity.

This is the case in Bathers (2025), Study for a Week of Sundays (2026), and the large canvas Vie et mœurs des oiseaux / The Life and Habits of Birds (2026). With its subdued palette and tarnished surface, the latter produces a form of continuity borrowed from cinema. Two figures—perhaps lovers—share an intimate moment in a domestic interior rendered with careful recognizability. It is unclear what is actually taking place, and, importantly, we do not want to know. They look at a screen; we look at a canvas. That is all the information required. The difference is that voyeurism is now fully exposed. We are looking at something that resembles us—uncomfortably so.

Where earlier works relied on patches of texture, cellular formations, and haptic, tentacular shapes, this section of the exhibition introduces a more structured core. It no longer plays as insistently on the reverberation of obedience. Instead, it shifts toward legibility while maintaining a degree of opacity—less coercive, but also less vertiginous.

More broadly, much of Oreian’s oeuvre to date can be read as a speculative investigation into the skin of painting—pushed to an extent that at times deprives it of oxygen, yet also continually reasserts what painting is: arrival, hunger, a mystification of collapse and rebirth that insists on being encountered with the naked eye. If there ever was such a thing as the naked eye.